Health and Healing

Tuesday 12 September 2023

A look at Peterborough's changing health services from C.1125 to the present day.

Peterborough has a long record of what we could call health services today, with hospitals like St Leonards which was established around 900 years ago! Let's explore some of Peterborough's healing history, and how it compares to today.

A Roman Healing Well?

Most of the archaeological digs in the 21st century are small digs in advance of development. One of these digs took place in Bretton before the Eagle Wood Neurological Care Centre was opened. An unexpected find was a Roman Healing well and evidence of a settlement lasting around 400 years.

The Eagle Wood site is directly south of Grimeshaw Wood and to the east of the Milton Estate. Originally situated within Walton parish, the area was once heavily wooded. Since the 1960s the area has been part of the Bretton township.

The archaeological dig in advance of the Eagle Wood centre identified an Iron Age Settlement dating from approximately 100BC. The site continued to be used until around 300AD which was during Roman occupation of the area. Finds included coins, shoes, pots and animal bones, but most impressive is a stone-lined tank. At approximately 2.5 metres deep, the tank was probably a roman healing well. It is of national interest because of its uniqueness. Nearby, other artefacts have been discovered including an amulet, a pendant and an ice skate. An aisled barn and evidence of field systems were also discovered in the area, showing that people were living nearby.

The bottom of the stone-lined tank has been left in place, but the upper stones of the tank have been incorporated into landscaping of the site. The artefacts discovered during the dig can be viewed in the reception of the Eagle Wood Neurological Care Centre.

C.1125AD St Leonard’s Leper Hospital Established

Founded before 1125, St Leonard's Hospital was a leper (or lazar) house supported through almsgiving by Peterborough Abbey. Leprosy was particularly prevalent at this time though such houses also provided for other categories of ill and destitute people. St Leonard’s became known as “The Spital”, Spital was a Middle English term used to describe a hospital or its endowed land.

It was still in existence in the 16th century and is assumed to have closed at the time of the dissolution of the monastery.

It was probably located close to the northern end of Peterborough railway station with its own cemetery to the west which is likely to have housed some of those who died from the plague. It gave its name to St Leonard’s Street which was the section of Bourges Boulevard which now runs past the station.

Associated with the hospital was a healing spring or well which was still documented in the mid 17th century.

C.1177 The Hospital of St Thomas the Martyr

Said to have been founded at the gates of Peterborough monastery, the Hospital of St Thomas the Martyr was originally named St Thomas of Canterbury. It was founded by Abbot William of Waterville (1155-75) and provided a hospital for the poor. Abbot Benedict completed the building between 1177 and 1194 and Abbot Acharius granted money from the chapel of St Thomas the Martyr (a huge draw to pilgrims and therefore a good source of income) to pay for the nuns who cared for the patients and to provide provisions for the sick. Many of the pilgrims visiting the abbey at this time would have been unwell, so this was a rather clever plan to use pilgrims' money to pay for the sick.

C.1294 Southorpe Hospital

Southorpe is a small linear hamlet to the south of Barnack. Today there are few houses in the hamlet, which has, until recently, maintained a strong agricultural heart based around the farms on the main road. However, there is a greater history to Southorpe, most of which remains as earthworks.

To the south of the hamlet are the remains of fishponds, clearly identified on the ground, as well as on maps and aerial photographs. The fishponds were thought to belong to Southorpe Hall, but may date to an earlier medieval hospital. Southorpe hospital was created by Peterborough Abbey, with a reference made to it in 1294, but very little else is known about the hospital or why it was sited there. Local belief is that the site, which is on the Hereward Way and adjacent to Ermine Street, was a popular route with pilgrims, which may explain its location.

1394 The Black Death comes to Peterborough

The Black Death (or the Great Pestilence as it was known then) hit Peterborough in 1349. This terrible disease, now called bubonic plague after the enlarged lymph nodes (buboes) resulting from the infection, is caused by an organism called Yersinia pestis carried by the fleas on black rats, though at the time it was thought to have been caused by bad air known as 'miasma'.

Approximately a third of the townspeople and 32 of the 64 monks at the monastery perished in a matter of weeks, and many of those who died were buried in mass burial pits to the west of the town and in the burial ground of the leper hospital of St Leonard. A higher proportion of monks died perhaps because they were helping tend to the sick.

The plague returned to Peterborough on many occasions causing a great deal of death and suffering until the last outbreak in 1665.

1857 House to Hospital

Following the death of Thomas Alderson Cooke in 1854 his Priestgate Mansion was sold to the 3rd Earl Fitzwilliam, who allowed it to be used as the city’s first hospital, the Peterborough Infirmary from 1857. The infirmary was run by a charitable trust. The house remained Peterborough's Infirmary until 1928.

Dr Commissiong's Misfortunes

Doctor Joseph Watson Comissiong was a much loved member of the Peterborough medical support network. He ran his own practice, as well as providing surgery, working as a 'man midwife', working as a coroner and being the vaccination officer for Werrington and Walton. However, his life was not one of ease and enjoyment, but of difficulty and tragedy.

Dr Comissiong arrived in the city on 25th June 1858 with his wife Mary Ann, daughter Ada and sons Joseph and Walter. They would have another three children whilst in Peterborough, but tragedy stayed close to their door. Their son Walter sadly died at the age of twenty three months, a few weeks before his brother Arthur was born. Dr Comissiong's surgery was in his family home and his children often ran into the surgery from the kitchen. On one occasion Walter helped himself to a bottle of hydrocyanic acid which was in a cupboard. The nursemaid heard him scream from the kitchen and found the boy face down and frothing at the mouth. He died swiftly, a verdict of accidental death poisoning being reached at the inquest. Arthur preceded the birth of his brother Herbert and sister Mary Ann; Herbert was born without the use of his legs, being described as lame in the census. Shortly after Mary Ann's birth Arthur died at the age of 5 in 1865.

Five years later on the 24th July 1870, Mary Ann, the wife of Dr Comissiong, died. She was 36 and left behind a husband and four children. Four years later, whilst in Bradford, eldest daughter Ada died at the age of 19 only a matter of weeks after Dr Comissiong filed for liquidation. The reason that we know the exact date he had arrived in the city is that he already had a stream of debtors following his every move before he arrived, this information being published in the paper. His debts were considerable and remained with him whilst he lived in the city.

By the 1881 census Dr Comissiong had moved to a smaller residence and was benefiting from the services of a housekeeper, who remained with him through to the 1891 census. Whilst many couples cohabited under the pretence of being an employer and housekeeper, there is no evidence to support this claim. He died aged 63 in 1894 and had a well-attended funeral.

Of Doctor Comissiong's three surviving children, Joseph moved to Yorkshire where he became a marine engineer with his wife and children, Mary Ann married and lived in Peterborough and Herbert gained employment as a wood merchant's labourer in the city.

Doctor Joseph Watson Comissiong Dies

Doctor Joseph Watson Comissiong was born in 1831 in Grenada in the West Indies and was Peterborough's first black doctor. He travelled to England from Grenada with his friend John and studied medicine at King's College in London, as the 1851 census recorded. By 1861 he was living on Lincoln Road in Peterborough and was married with three children, the youngest being born in Peterborough in 1860. He described himself as a 'Member of the Royal College of Surgeons of London' and as a General Practitioner.

He worked as a GP in Peterborough and often worked as a coroner on suspicious and unusual deaths in the city. He was connected to Peterborough Infirmary and was one of the stewards at the infirmary ball in 1864, which was run to raise money for the institution. He was also chosen as the public vaccinator for Werrington and Walton in the same year.

In his spare time he was a keen musician, a member of a local brass band and the Amateur Dramatic Society. He was also a member of the Freemasons from 1862 in St Peter's Lodge and a member of the local Engineers Volunteer Corp, as was Dr Thomas Walker.

He died on 12th April 1894 and local papers marked the occasion by stating 'he was almost the idol of the New England people, who went so far as to propose buying him a horse and carriage. He was most generous in his disposition and he was greatly respected by the poor.' A statement on his funeral read:

'Mr J W Commissiong, surgeon of Peterboro', died at Millfield, Peterboro', on Thursday week. he had practised in the city for many years. He held the commission of surgeon to the Peterboro' Engineer Volunteer Corps, was also medical officer for the Railway Men's Club, and was an accomplished musician. The funeral took place in the cemetery on Tuesday, and was attended by a large number of spectators. Many of the members of the N. E. V. Corps, including Major Deacon and Dr Cane, attended in uniform as a mark of respect to their late officer, and a great many of the deceased gentleman's former patients were also present to witness the obsequies.'

1884 Peterborough Infirmary Fire

At midday on 9th May 1884 there was a disastrous fire at Peterborough Infirmary in Priestgate. The infirmary contained 100 patients who were hauled outside onto the grass to safety, along with as much medical equipment as could be saved. Some of the first newspaper reports suggested that patients were still inside the building when the roof collapsed, but these rumours were unfounded and everybody was accounted for; the patients were driven away in cabs or moved to a building supplied by the Dean and Chapter. The fire was caused by an overheated flue and caused £5,000 worth of damage. The lack of accessible water to extinguish the fire and deficiencies of the Fire Brigade led to the formation of the Peterborough Volunteer Fire Brigade.

Father Christmas Spends Christmas in Hospital

Alfred Caleb Taylor is best known for his pioneering x-ray work in Peterborough, and rightly so, but there is another story worthy of mention, that demonstrates his kind nature.

On Christmas Day 1890 Mr Taylor, who was a dispenser at Peterborough Infirmary, visited the children who had to spend Christmas in hospital. He dressed as Father Christmas 'with a large hirsute appendage of cotton wool'1 or cotton wool beard. Unfortunately, as he was handing out presents from the Christmas Tree to the children, his beard caught alight 'and his moustache, eyelashes and eyebrows were singed off, and his face, ears and head were badly burned.'2 Thankfully expert care was right to hand and he avoided any lasting injuries from the incident, as his later photograph demonstrates.

This event happened only a couple of years after a fire engulfed the infirmary, so it was fortunate that nothing else set alight and no damage occurred to the building.

Sadly no image of A.C.Taylor as father christmas is currently in our collections, however an image taken in the early 1930's at Peterborough Memorial Hospital paints what must of have been a similar scene.

A Cautionary Tale About Plums

Five-year-old Master Bellamy had watched his mother cut up plums to make into jam. When she left the kitchen he gobbled up what he could, which was unfortunately 28 plum stones! Thankfully he relayed the information to his mother who sped him to Peterborough Infirmary in Priestgate. There he received not one but two emetics, bringing up 14 stones each time. No harm appeared to have been caused by his actions, but he may well have avoided Plum jam for a while!

Plum stones contain small levels of amygdalin which converts into hydrogen cyanide in the body. Even though plum stones contain only around 9mg of amygdalin, 28 stones in the body of a 5-year-old could be enough to cause serious problems.

1895 X-ray Exploration

Peterborough Infirmary was one of the first locations in the country to use X-rays. Alfred Caleb Taylor, the infirmary’s dispenser and secretary, was a keen photographer and, excited by the discovery of X-rays in the final weeks of 1895, created his own X-ray equipment in the infirmary. Images produced were positives, rather than the negatives that are produced today and they were taken to identify foreign bodies as well as broken bones.

In 1911 a two-year-old girl named Mona Ray was taken to Peterborough Infirmary from Ramsey. She was X-rayed and discovered to have swallowed a hair pin, which had travelled through to her intestines, no doubt causing her some discomfort. Thanks to the X-ray the doctors knew exactly where to operate and quickly removed the offending hair pin. Thankfully the operation was a success and the girl was described as ‘recovering splendidly.’

1896 Alfred Caleb Taylor and the First X Ray Machine Outside London

Alfred Caleb Taylor was born in Newark-on-Trent, Nottinghamshire in 1861 and came to Peterborough aged ten. He worked at the Peterborough Infirmary on Priestgate from 1880 as a dispenser. He also served as Secretary of the Infirmary from 1889 until his retirement in 1926.

Mr Taylor had a keen interest in photography and chaired the Peterborough Photographic Society. This carried over into an interest in X-rays being an early advocate of X-ray technology. In 1896 he designed and built his own equipment under the stairs in the infirmary. This device, the first X-ray machine in the United Kingdom outside London, was powered by accumulators. They were recharged at a local flour mill as there was no public electricity supply at that time. When an electricity supply was available in Peterborough, Mr Harry Cox, from London, was consulted regarding a larger installation. Many people made donations towards the new x-ray apparatus; Mr Andrew Carnegie, Peterborough’s first Freeman kindly donated £125 towards the installation. As with the photography of the time the images produced by the X-ray machines were positives rather than negatives.

Radiography

As the science of radiography was so new, the danger of exposure to X-rays was unknown. Taylor worked with the x-rays so often, that it badly affected his health. He contracted radiation poisoning resulting in the loss of four fingers, three on the left hand and one on the right. Despite this he never expressed any regrets and said,

“I have only done my duty, and if I have sacrificed bits of my fingers so that I am not able to tie up my shoes laces, I feel I have been compensated, for I have loved the x-ray work and its excitements. For all the trouble I had at the beginning I have been more than compensated by your appreciation, and although I have lost bits of fingers, I would still do the same if I had my life to come again.”

Alfred Caleb Taylor died on the 6th of July 1927, a pioneer and martyr.

1897 Victorian Operating Theatre

The first purpose-built operating theatre was opened in 1897. It was built as an extension to Peterborough Infirmary.

It provided state of the art care for the people of Peterborough, incorporating the most up to date medical ideas. These ideas included the use of anaesthesia and keeping the theatre meticulously clean. So many things we take for granted in the twenty-first century were new ideas to the Victorians. However, these new ideas still save lives now. It was originally lit by gas lighting and had a glass roof to maximise light.

The funds to build the operating theatre came from two Peterborough women who chose to remain anonymous, they went by the name 'Heliotrope'.

The Victorian operating theatre is open to visitors to Peterborough Museum. It still contains many of its original features including the glazed white tiles. Replicas of the tools used in the past are also on show. A small case details some of the people who worked in the operating theatre.

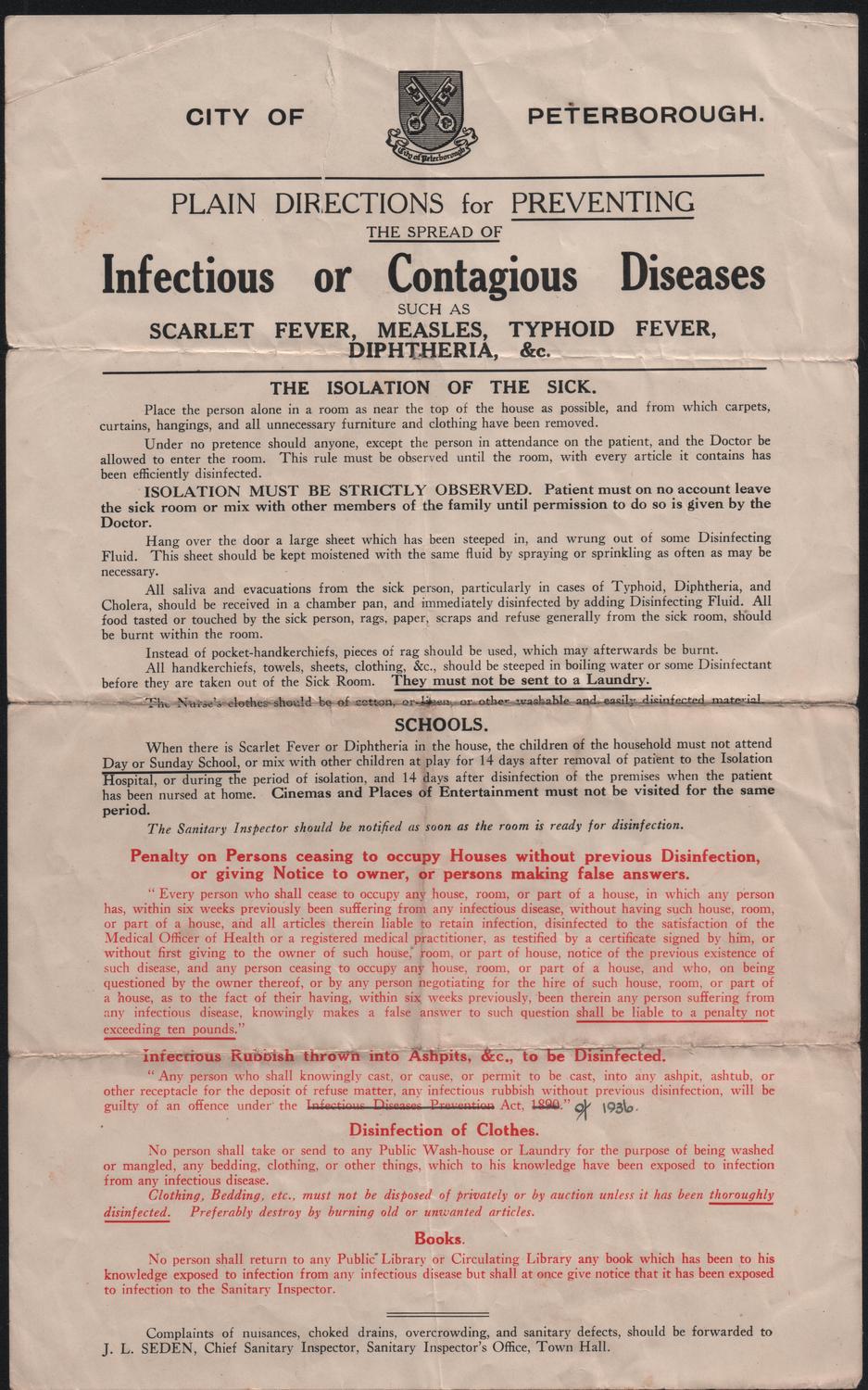

1901 St Peter's Isolation Hospital Opens

St Peter's Isolation Hospital (also known as Peterborough Fever Hospital) opened in 1901 near Potters Way in Fengate. It was opened in response to widespread outbreaks of infectious diseases like Diphtheria and Scarlet Fever. It closed in 1981.

The leaflet below was donated to the Museum by a patient of St Peter's Isolation Hospital. The donor had contracted scarlet fever in 1948 at the age of five and was taken to isolation hospital at Fengate. When their parents visited they were required to stay behind glass to prevent the spread of the infection. The donor remembers having to miss their sister's wedding due to the illness. The leaflet was issued by the City of Peterborough and references the Sanitation Inspector, and details isolation and disinfection procedures in addition to penalties imposed for not following disinfection and disease notification procedures.

1904 Death of Florence Saunders

Florence Saunders was the youngest daughter of Augustus Saunders, Dean of Peterborough. Inspired by her many visits to the poor and sick as a child accompanying her father, she joined the Evelina Hospital for Sick Children to become a nurse. On her return to Peterborough she committed herself to caring for the sick using modern remedies. In 1884 she founded the Peterborough District Nursing Association to bring modern nursing to more people.

She died aged only 48 years old and her obituary in the Peterborough Advertiser read:

"Notwithstanding the fact that her duties as Superintendent occupied much of her time, Miss Saunders never gave up her active work of visiting, soothing and healing. almost to the last she moved about in the much-loved uniform among her humble friends."

A memorial in her name was hung on the building created by Miss Saunders as the first purpose-built nursing home in the city. The building, a neo-gothic design probably built by John Thompson is now surrounded by the Bishop Road Gardens.

1928 Peterborough Memorial Hospital Opens

The Memorial Hospital was opened by Field Marshal Sir William Robertson in 1928, as a memorial to those of the city and the 6th Northamptonshire Regiment who died in the First World War, it replaced the Peterborough Infirmary; the building that had housed the infirmary becoming Peterborough Museum.

When the Memorial Hospital opened it had six wards in three blocks: separate male and female surgical and medical wards, an accident ward and a children's ward. It had 150 beds, two operating theatres, a radiology department, a small casualty department, and outpatients, physiotherapy, occupational therapy and speech therapy departments. A separate hospital at Fengate was used to treat infectious diseases.

The National Health Service is Born

On the 5th of July 1948, Health Secretary Aneurin Bevan launched the National Health Service (NHS) at Park Hospital in Manchester. Its ethos was to provide health services for all, free at the point of delivery. For the first time, hospitals, doctors, nurses, pharmacists, opticians and dentists were brought together, nationally, in one organisation.

The Peterborough Memorial hospital was transferred to the newly formed National Health Service in 1948.

1968 Opening of Peterborough District Hospital.

After the Second World war the Memorial Hospital was no longer big enough to deal with Peterborough's health needs and in 1968 it closed and Peterborough District Hospital opened, incorporating the Memorial Hospital as the Memorial Wing.

Peterborough District Hospital had 357 beds, five operating theatres, an accident and emergency department, outpatients clinics, as well as radiology and pathology services, an intensive care unit and surgical and medical specialist units.

1988 Opening of the Edith Cavell Hospital

In 1988 Edith Cavell Hospital in Bretton was opened by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, it was built to complement the services provided by Peterborough District Hospital.

2010 Opening of Peterborough City Hospital

In 2010 the District Hospital was closed and replaced by the Peterborough City Hospital which opened to patients in November of the same year. It also replaced the Edith Cavell Hospital, being built on the Edith Cavell site in Bretton. The hospital was built under the Private Finance Initiative.

The Hospital has 612 beds and, as well as the usual facilities, it also houses a Cancer Centre, a Cardiology Centre, a Women’s and Children’s Unit and Adult and Paediatric Emergency Centres.

The official opening was carried out by the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge in November 2012.

References:

'Hospitals: St Leonard & St Thomas Martyr, Peterborough', in A History of the County of Northampton: Volume 2, ed. R M Serjeantson and W R D Adkins (London, 1906), p. 162. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.... [accessed 12 July 2019].

A Peterborough Cathedral Timeline https://www.peterborough-cathedral.org.uk/history.aspx [accessed 12 July 2019]

A List of the Abbots of Peterborough https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abbot_of_Peterborough [accessed 12 July 2019]

Peterborough Advertiser, 7th April 1860, p6, c6

Stamford Mercury, Friday 19th February 1864, p1 col 1

Peterborough Standard, Saturday 14th April 1894, p5 col 7

Stamford Mercury, Friday 20th April 1894, p4, col 3

Ancestry.com:

1851 census, Middlesex, St Pancras, Gray's Inn Lane, 11, slide 9

1861 census, Northamptonshire, Peterborough St John the Baptist, District 13, slide 30

Bridport News, Friday 9th January 1891, p 7, col 3

North Devon Journal, Thursday 8th January 1891, p 2, col 5

Peterborough Swallowing Plum-Stones, Northampton Mercury, Friday 31st August 1894, p. 8.

Peterborough Advertiser, Saturday 28th Jan 1911, p5, col 5

https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/5982837 - Paul Bryan

Peterborough Museum

https://historic-hospitals.com/english-hospitals-rchme-survey/cambridgeshire/

https://www.peterboroughimages.co.uk/st-peters-isolation-hospital-fengate/

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57a08d91e5274a31e000192c/The-history-and-development-of-the-UK-NHS.pdf

Peterborough Today. 15 November 2012

https://www.nwangliaft.nhs.uk/our-hospitals/peterborough-city-hospital/